- Home

- Mark Schultz

Foxcatcher Page 10

Foxcatcher Read online

Page 10

Andre Metzger, our other national champion in 1982, had also been a senior the season before. No other wrestler on the team could relate to the pressure to defend that I faced. Dave did his best to help when we did have time to talk, and Andre had become an assistant coach, too, so he was still around. But unless someone is actually going through the same pressure at the same time, it just isn’t the same.

With our team losing two national champions, Coach Abel needed me to be a big winner for the team. The most points a wrestler could score for his team was six, with a pin, forfeit, injury default, or a disqualification. But I wasn’t a big pinner. I would estimate that only about 10 percent of my wins in college came by pin. I felt overburdened from the pressure I was placing on myself to match my individual accomplishments from the previous two years. And now the coach and team needed me to be even better than I had been before!

For my own sake, I had to go out as a winner. I couldn’t imagine anything worse than winning two national championships and then not winning my senior year. Given the choice, I would have opted to have not won the previous two years if it would have guaranteed a title as a senior. One title in my final chance would have meant more than two earlier ones.

To this day, I have recurring nightmares about my senior year. The details vary, but the way they play out tends to go something like this: I’m having to defend my back-to-back titles, it’s two weeks out from the NCAAs, and I’ve forgotten to work out and am trying to figure out how to win without being in shape. I consider stabbing myself in the leg or crashing my car on purpose to get out of the tournament.

In some of my nightmares, I am at the tournament weighing in to wrestle the next day and I’m coming off an injury that has me out of shape. I have probably had that particular nightmare at least fifty times.

Every time I wake up from such a nightmare, I thank God it was only a dream.

Port Robertson was a former wrestling coach who worked in the OU athletic department as an administrator. I didn’t know what his official title was, but to me he was “Lord of Discipline” and “Ruler of the Jock Dorms.” Port liked me, and when I found out that a single room had opened in the dorm, I asked Port if I could have it. He gave it to me.

I spent every night after practice alone in my room. It was depressing. I had tried to stick to myself before, but I became more introverted that year. I bought a cheap black-and-white TV for my room to have as my company. I rarely talked to anyone in the dorm. I’ve never felt more alone and isolated than I did that year, and it was self-inflicted.

—

I started the season strong, including beating every opponent badly in a Las Vegas tournament, but I soon complicated my situation during an interview with one of Oklahoma’s statewide TV stations.

I did few interviews in my time at OU, and I really hadn’t wanted to do any that year for sure. But the reporter was the daughter of a Sooners alum who had paid Dave and me to drive an RV to Dallas so he and his drinking buddies would have a place to hang out and drink the weekend of the annual Oklahoma-Texas football game. I agreed to the interview only to return the favor for the reporter’s father.

I sat down for the interview and the cameraman placed his camera on a table. I hadn’t seen him push any buttons, so I assumed the interview hadn’t started. The reporter’s first question was about how I liked OU. Another bad assumption on my part: I assumed she was just making some preinterview chitchat.

“I wish I would have gone somewhere like Iowa where the coach cared more about his athletes,” I told her.

After I said that, the cameraman picked up his camera and turned the lights on. The interview lasted about forty-five minutes. The only part that made the news that night was what I had said about Coach Abel in what I believed to be an off-the-record comment.

I wasn’t being totally serious with what I said about Coach. Part of it was me speaking out of my depression and prolonged frustration.

Coach Abel was in the middle of a difficult divorce and wrapped in his own little world at the time. The biggest impact I saw from his divorce process was that he wasn’t able to spend the time I thought he needed to be spending with me, especially in light of how lonely I already felt.

I had no idea how consuming a divorce could be. Since then, I’ve had two myself and have discovered just how much one can dominate your time and distract from your regular activities.

My comment, predictably, created a firestorm. Alumni started calling Coach Abel to ask what was going on under his watch, and some were telling him they were going to stop donating money to his program.

Coach dragged me into his office the next day. “What the hell is wrong with you?! Is that the way you want it?!”

I was so into not displaying any weakness—and I also was a little ticked at him because I wrongly thought he was neglecting me—that I responded, “Yeah.”

Our relationship grew cold instantly. I rarely talked to Coach after that.

My attitude and wrestling started going downhill. I began sporadically showing up in the wrestling room. I went back home to Oregon over Christmas and missed the Midlands tournament and three duals. My biggest threat to winning the national championship—at least as far as other wrestlers went—was Duane Goldman of Iowa. Goldman was a freshman, so we hadn’t wrestled each other before, and I didn’t want him to have any idea what to expect from me until we met in the NCAAs, if that was to be the case.

The team didn’t matter to me. I was out for myself and felt that I was protecting my title, not fighting for another one. In my mind, I had nothing to gain and everything—and I mean everything—to lose.

I won the Big 8 championship in qualifying for my fourth NCAA tournament, in Oklahoma City that year. I came down with strep throat just as the tournament started. A media photographer took a picture of me warming up with my tongue sticking out, and my tongue was white, it was so dry.

I struggled in my first-round match, defeating unseeded Scott Giacobbe of Old Dominion University 8–5. In the second round, I faced number-twelve seed Bob Harr of Penn State. In the first round, I got him in the Schultz front headlock and choked him out, turned him over, and pinned him. But the refs only gave me a takedown. Harr woke up mad and spent the rest of the match attacking like crazy. I beat him 11–6 but had to deal with a pissed-off wrestler the entire match. The third round produced my only “easy” win, with a 15–4 defeat of unseeded Jeff Turner from Lehigh University.

I drew Ohio State’s Ed Potokar in the semifinals. I was 25-0 that season with my reduced schedule. Ed had broken the Ohio State record for victories in a season with his 49-1 record. Winning our semifinal match would have given him fifty wins.

I led Potokar 4–2 in the third period, and both of his points had come for my being penalized for stalling by referee Pat Lovell. I was on top of Potokar with sixteen seconds to go and all I had to do was ride him out and I would be in the finals. But then Lovell hit me with another stalling call, giving Ed two points and tying the score at 4.

Lovell had been a heavyweight wrestler before becoming a ref. He was from the San Francisco Bay Area, like me, and we were friends. We’d even had lunch together at his home. Now I’ll never forget Pat because of that last stalling call that tied the match. I’m not saying his call was wrong; I’m just saying I’ll never forget it.

Pat’s call stopped the match so we could go back to the center of the mat. Potokar was jumping up and down, superpumped. I, on the other hand, was almost scared out of my mind. We were tied and my opponent had yet to score a technical point. If Potokar managed to pull off an escape from the bottom, he would beat me 5–4 and my senior year and my life would be ruined.

When Pat blew the whistle to resume the match, Potokar exploded from the bottom. He was riding all the momentum of the late call that had tied the match. I was riding a bucking bronco.

Finally, Potokar stood up, broke my grip,

and spun behind me. But right before the ref could call a two-point reversal, I did something I had never done: I squatted like a frog and dove straight backward, like a back dive off a diving board, hoping to grab hold of something. I hooked a finger into the loop of Potokar’s shoelace, clawed my way up his leg, and held on like my life depended on maintaining that grip. The final seconds ticked off the clock and we went into overtime.

Potokar still couldn’t manage a technical point in overtime, and with no stalling calls against me, I outscored him 6–0 in overtime to advance.

—

Goldman, the second seed and freshman sensation, defeated Perry Hummel in the other semifinal. Thanks to my Christmas in Oregon, I hadn’t wrestled against Goldman, and that gave me an advantage going into the finals, in my opinion. The more often wrestlers face each other, the closer their matches tend to become. If I had wrestled Goldman previously, I think a certain amount of my aura could have been diminished merely by his getting onto the mat with me.

Maybe he wasn’t thinking that way, but I was, and it gave me a psychological boost going back to the hotel the eve of our final.

Frankly, I needed every edge I could get because a memory of the NCAAs from my freshman year at UCLA kept haunting me. Mike Land was a senior at Iowa State and a defending national champion. In the 1979 finals, he faced a freshman from Lehigh named Darryl Burley. Land had won eighty-four consecutive matches, but in his last time on the mat in college, he lost to the freshman.

Now here I was, the senior defending champion everyone expected to win going up against a freshman in the finals.

So much for a good night’s sleep.

A couple of hours before the finals started, I was sitting in my hotel room with Clinton Burke, our 134-pounder and the only other Sooner who would be wrestling for a championship. There was a knock on the door and Clinton opened it. We were only a half hour’s drive from Norman, and all these friends of Clinton’s came streaming into our room, laughing and drinking and smoking.

I’m sitting there on my bed thinking, These people are going to kill us mentally.

It was way too early to celebrate. Or be happy even. Being happy could ruin my mental state as I prepared for the match. Clinton seemed to have no intention of asking his friends to leave, so I grabbed my gear and headed to the arena much earlier than I had wanted to.

The commentator from Wide World of Sports was going around interviewing all the finalists at the arena. For me, that was no time to be talking. I gave one-word answers to his first three questions. Visibly frustrated, he said, “This is impossible. I can’t do it.” I got up and walked away to be by myself, just as I preferred.

Right before the first final, Clinton seemed to realize the enormity of wrestling in the finals. I could see him in the corner of the warm-up room looking all emotional. I wasn’t sure, but it looked as though he was crying. Andre walked over to Clinton and told him he had to snap out of it. I couldn’t be a part of that scene and stayed away from them. Clinton lost his match by two points. That left me as OU’s only hope for a championship in 1983.

Coach Abel and Coach Humphrey had warned me about stalling. They said the refs thought I had been stalling too much in the tournament and had met and decided to show me no mercy in the finals. Then in the final moments before my match, Dave told me that the refs were going to be watching me very closely for stalling and wouldn’t cut me any slack.

Jeez, did anyone else in the arena want to warn me about stalling?

From the moment Goldman and I met on the mat, I could sense he had already decided I was supposed to win. It’s difficult to put into words, but there was something in his eyes and body language that gave it away.

Goldman’s escape attempts seemed halfhearted, and he was easier to hold down than anyone I had beaten coming through the bracket. My only concern came from all those stalling warnings. I was called three times—the first as a warning and the next two for one point each. I didn’t think Goldman would score on me otherwise, but locked in a close match and knowing the refs were paying extra attention to me, I was worried that a repeat of the semifinals match against Potokar would happen. It didn’t, though, and with four minutes of riding time, I won 4–2 and for the third consecutive year defeated an Iowa Hawkeye to win the NCAA championship.

One year after taking part in one of the most exciting matches in college wrestling history, I had just won the most boring match of that year’s finals. But I didn’t care, because I had won. I had pulled off my biggest escape as a wrestler—the escape from the pressure and expectations that had weighed heavily on my chest for a full year.

I stood there with my arms outstretched like a bird. I finally felt released, unlatched from my burdens, free to fly away and leave behind all the junk that had accumulated to make my senior season pure hell.

Then I did something I’d done rarely during the season: I smiled.

I thanked God repeatedly.

Before taking the mat and winning my second championship, I had prayed that God would take my life if I lost. Now, one year later, and only six years after taking up the sport of wrestling, I stood there, soaking in the glory of being cheered as a three-time NCAA champion.

God could have taken my life right then and there, too, if he wanted and I would have died a happy person. There hadn’t been many times in my life when I could have said that.

CHAPTER 8

Brothers, Olympians

There’s that old expression about seeing the light at the end of the tunnel. Why doesn’t anyone talk about what happens when you exit the tunnel?

My senior year had been my tunnel, and to help make it through, I had kept telling myself that there was a light at the end. If I came out on the other end with that third NCAA championship in hand, I thought I would retire and be happy the rest of my life. I would have been content with calling my senior year the final chapter and sending that book off to the printer.

But Dave had other plans for us.

Dave had won his championship as a senior and had earned All-American status all three seasons he was able to compete. But he didn’t care too much for collegiate wrestling. He was better at freestyle wrestling. Collegiate, or folkstyle, wrestling required more of a control-oriented, grinding style. It favored super-conditioned athletes with strong upper bodies that allowed them to hold opponents on their back for near fall points and to accumulate riding time. Also, the option of the down position benefited wrestlers who could ride and escape.

Freestyle, however, did not have the down position or points for escapes and riding time. Freestyle featured more wrestling on your feet and favored wrestlers who were better at takedowns, throws, and turns. Dave was one of the best in the world at all three. Dave won eight freestyle national championships (plus two Greco-Roman) and was named the nation’s top freestyle wrestler four times. Dave’s body and wrestling style perfectly suited freestyle.

Dave tried to talk me into competing at the US Open, but I was so burned out from my senior season that I had no desire to go. At that point, I couldn’t imagine putting my body and mind through another competition, but Dave wouldn’t stop bugging me. He was not going to let me quit wrestling and convinced me to go with him that summer to try out in Iowa City for the United States’ Worlds team. I went, not sure it was what I wanted to be doing, and we both made the team, with me defeating Duane Goldman again for my spot.

Dave and I graduated from Oklahoma with degrees in exercise science. I don’t know how it is in most colleges now, but back then exercise science was a more academic way of saying PE. I used to joke that I actually was majoring in eligibility.

If we had gone the astrophysics route and had to study a lot more, we wouldn’t have become nearly as good as wrestlers as we did. But wrestling, not education, was the reason we were at Oklahoma. Although jobs in astrophysics would have paid more after college.

Former college w

restlers who wanted to compete in freestyle had few options. The common route was to try to find an assistant coach’s position at a college that would pay you poorly but at least give you a place to work out and provide wrestlers to work out against.

No such opportunity existed at Oklahoma. Coach Abel wouldn’t hire us because he said we weren’t team players. He was correct, at least in my case. My interview with the TV station didn’t help our job prospects, either.

We did, however, receive an offer from Chris Horpel to coach with him at Stanford.

I had no ties to Oklahoma, and certainly no reason to stay. I gave the other wrestlers everything I possessed except for the clothes I could fit into one bag, hopped on my Honda 400 motorcycle, and split.

About half a mile west of Oklahoma City, I pulled over to the side of Interstate 40, shut off my bike, stepped off, and looked back toward the city skyline. I stood there for about twenty minutes reflecting on my time in that state, about my commitment to sacrifice my life there if that’s what it would take to make it there. Dying trying would have been more acceptable than failing.

Do or die, right?

Four years later, I was still standing, winner of the national championship all three years I competed. I had won my final forty-four matches as a Sooner. By going 27-0 my last season in crimson and cream, I had broken the school record for most wins in an undefeated season, a record that stood for seventeen years. I had never lost a match at home and had avenged all my losses against my greatest opponents.

Satisfied that all my demons had been exorcised, I got back on my bike and headed home.

—

Dave and I were able to find a home owner who rented us rooms for a great price: our dad, who rented out rooms/apartments in his house. Dave and his wife took one room upstairs, and I had another. It was great to be back under the same roof as my brother.

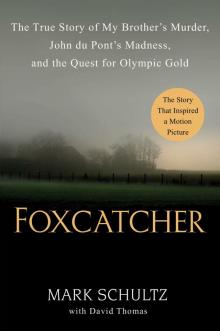

Foxcatcher

Foxcatcher